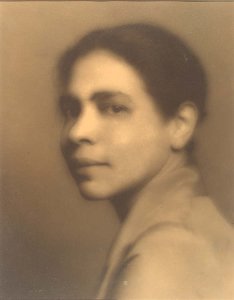

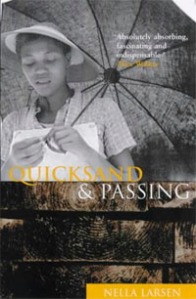

Nella Larsen was a modern woman who “feels that people of the artistic type have a definite chance to help solve the race problem”[1]; she wrote from the epicentre of the Harlem Renaissance, winning an award from the Harmon Foundation in 1928 for “the best piece of fiction to come out of Negro America since Chesnutt”[2] and she was the first black woman to win a Guggenheim award for creative writing in 1930. It is her critically acclaimed novels Quicksand and Passing that afford Larsen her reputation as “the major novelist of […] the Harlem Renaissance”[3] because of the way in which these texts indisputably engage with the major tropes of the period – exploring the intricate relationship between race, gender, class and sexuality – thus allowing her to discretely critique “the gendered and sexual double standards of the well-to-do black middle classes of which she was a part”[4], exploring how these factors complicated the ‘New Negro’ identity construction, leaving many coloured people like herself on a quest for their sense of belonging within the cultural climate. Her texts are subtly persuasive and powerfully poignant when situated both within the context of the Harlem Renaissance and in contemporary debates about race, gender, class and sexuality, thus arguably rendering her novels “contemporary and timeless”[5]. She does this by manipulating existing literary traditions concerning race, for instance the reductive ‘tragic mulatto’ caricature and the autobiographical elements of her texts which are employed in order to realise her ambitions for a resolution to racism and sexism.

Larsen questions racial outlines via the problematic notion of the ‘colour line’ in both Quicksand and Passing, exploring the difficulties encountered by ‘mulatto’ figures such as her protagonists Helga Crane, Clare Kendry and Irene Redfield. Clare and Irene express polarising attitudes towards race, with Irene promoting the racial pride of the emerging Garveyism of the time through her “mounting anger and indignation”[6] over Bellew’s overt racism, while Clare muses “I’ve often wondered why more coloured girls […] never ‘passed’ over. It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do”[7], thus perpetuating the perceived racial hierarchy whilst simultaneously refuting the embracement of race seen in other strains of the movement – for instance Countee Cullen’s Edenic description of Africa in his devotional poem to his home land. These conflicting attitudes towards race arguably embody Larsen’s own internal conflict over the morality of ‘passing’ and act as reliable resources which demonstrate some of the attitudes towards race at the time. Moreover, “passing is sometimes thematized as the taking of a new, not necessarily racialized, identity in various locales”[8] as Helga Crane does in Quicksand. It is the text’s autobiographical elements such as Crane’s Danish heritage and the trope of European exploration before a return to ‘home’ in Harlem that allow Larsen to traverse the concepts of trans-nationality within the Harlem Renaissance which assisted African Americans in reconciling their racial identities. This theme echoes that of Claude McKay’s best-selling Home to Harlem which also entertains the idea of European travel, thus likening Larsen’s fiction to those texts within the sphere of influential contemporary African American writing.

The tragic mulatto paradigm inspects the inextricably linked expectations of race and gender in nineteenth and twentieth century texts, rendering Larsen’s female protagonists doubly entrapped in a slave-like racial subordination and an archaic female inferiority. However, Larsen arguably manipulates this literary convention, with her protagonist Helga Crane rejecting the racial and patriarchal expectations of her character with the emphatic declarative “I’m not for sale”[9]. Arguably, despite her displays of female independence, Larsen’s protagonist is ultimately doomed, falling into motherhood and dying alone, therefore being permanently affected by her marital status and entrapped within the stereotypical constraints of her gender. It is this inability to “[round] off stories convincingly”[10] that many of her African American contemporaries shared[11] which perhaps demonstrates one fundamental problem; there was no solution to white racism. Larsen’s protagonists are fuelled by the contemporaneous issues of gender and sexuality, exploring their connection to race at the time by refuting the typically sexualised exotic “commodification of the black female body”[12] seen in African American poetry of the time such as ‘The Harlem Dancer’ by Claude McKay, in favour of an attempted sexual independence displayed by the subversive homoerotic undertones of Irene’s attention to the “lovely creature”[13] Clare and her “mesmeric”[14] eyes. This would have been shocking for contemporary audiences, who would have only experienced black female sexuality in slave narratives, with an oppressive white male influence, or in the previously stated exoticised manner. In this way, Larsen’s protagonists are “ill suited for the proscribed existence ordinated by whites for blacks”[15] and she displays a search for new boundaries to “the limited possibilities open to African American women during the 1920s”[16], and in doing so acts as a pioneer of her time, fearlessly navigating controversial, sometimes taboo notions of black female sexuality.

In conclusion, Larsen’s “emotional nomads”[17] appealed to the disenfranchised groups of the Harlem Renaissance, namely African American women. However, these characters – marginalised for their race and gender – appeal to “any woman who has searched for […] a job where she could be paid what she deserved (despite her ovaries), or sought to fashion a love […] based on respect and honor for self and partner”[18], and it is this engagement with ongoing disputes over not only gender, but all aspects of sociological taxonomy which allocates Larsen’s works their “eternal relevance”[19].

References

[1] Larson, Charles R. Introduction to The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. Anchor Books (New York, 2001) pp. xii

[2] DuBois, W. E. B. Quoted in Looking for Harlem: Urban Aesthetics in African American Literature by Maria Balshaw. Pluto Press (London, 2000) pp. 47

[3] Larson, Charles R. Introduction to The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. xii

[4] Balshaw, Maria. Looking for Harlem: Urban Aesthetics in African American Literature. pp. 53

[5] Golden, Marita. Foreword to The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. viii

[6] Larsen, Nella. Passing, in The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. 202

[7] Ibid. pp. 187

[8] Sherrard-Johnson, Cherene. Portraits of the New Negro Woman: Visual and Literary Culture in the Harlem Renaissance. Rutgers University Press (London, 2007) pp. 12

[9] Larsen, Nella. Quicksand, in The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. 117

[10] Larsen, Nella. Passing, in The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. 365

[11] Ibid. pp. 365

[12] Sherrard-Johnson, Cherene. Portraits of the New Negro Woman: Visual and Literary Culture in the Harlem Renaissance. pp. 11

[13] Larsen, Nella. Passing, in The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. 180

[14] Ibid. pp. 191

[15] Golden, Marita. Foreword to The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. vii

[16] Carroll, Annie Elizabeth. Word, Image and the New Negro: Representation and Identity in the Harlem Renaissance. Indiana University Press (Indiana, 2007) pp. 227

[17] Golden, Marita. Foreword to The Complete Fiction of Nella Larsen: Passing, Quicksand and the stories. pp. vii

[18] Ibid. pp. viii

[19] Ibid. pp. viii